Recent events surrounding the FDA's failure to approve Ampligen (yet again) for treating ME/CFS have pushed aside what was left of the media storm precipitated by the discovery, dismissal and ultimate disavowal of XMRV. The disappearance of the retrovirus from the scientific scene does not mean that XMRV is dead. It lives on, regenerated by Hillary Johnson.

The March issue of Discover magazine includes a tour de force of journalism, Hillary Johnson's stunning article on XMRV, the retrovirus that was claimed to cause not just ME/CFS (aka myalgic encephalomyelitis or, as it is known in the US, chronic fatigue syndrome), but some forms of prostate cancer as well. Ultimately, XMRV was exposed as a lab artifact, but not before creating a sensation, which Johnson vividly captures in her article.

In “Chasing the Shadow Virus,” Johnson leads us through the dramatic twists and turns of the XMRV debate, from the original elation at the discovery of the cause of ME/CFS, to the CDC's panic at the horrible prospect of a contaminated blood supply, to the “cottage industry” of researchers who were unable to find XMRV in ME/CFS patients, and finally to the humiliation and public disgrace of the research director of the Whittemore Peterson Institute, Judy Mikovits. Those who followed the XMRV debacle with bated breath already know the story. But do we know its implications?

Midway through her tale, Johnson puts her finger on the true significance of the XMRV scandal:

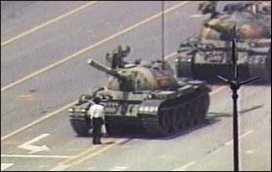

“After novelistic plot twists that included a police raid, an arrest, and a public tarring and feathering of the outspoken Mikovits, the scientific community is now convinced that XMRV was a false lead. Yet the expenditure of time and money to reach that conclusion was hardly an exercise in futility. The 2009 meeting in Bethesda marked the beginning of a change in the CFS cosmos, with a slew of prestigious scientists entering the field and government officials taking a more serious view of this formerly neglected disease. Moreover, the XMRV saga opened a rare window into the way scientists and government officials respond to findings that not only challenge the status quo but have profound implications for public health.”

Those final words are an echo of what Johnson wrote in Osler's Web, her brilliant exposé of the CDC's mishandling of the ME/CFS epidemic during the 1980s. The “window into the way scientists and government officials respond” is the same window that was opened seventeen years ago in Osler's Web, and in its even older predecessor, And the Band Played On. It is a window that reveals a glimpse of a murky and disorganized public health system whose job it is to ignore threats to its own complacency, to squelch any dissent from the ranks of upstart epidemics, and to starve researchers who are bold enough to investigate their causes. This has been the fate of ME/CFS for the last thirty years.

Johnson ends her article on a positive note. Ian Lipkin, the world-renowned virologist who proved that XMRV was not, indeed, the cause of ME/CFS (or anything else), credited Mikovits with “opening Pandora's box.”

“Right or wrong about this particular virus,” he says, “she deserved credit for awakening interest in CFS.”

Johnson's final words reflect that sentiment. “For a disease that has languished in a kind of political never-never land for at least one human generation, leaving millions profoundly disabled,” she writes, “that is significant progress.”

Whether this awakened interest is sufficient to spur concrete actions – the generation of NIH funding for research into the disease, changing the CDC's dismissive name, and convincing doctors that patients who suffer from its crippling effects are not just overworked, neurotic women who should have stayed at home rather than enter the work force – remains to be seen.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed